I mind my own business, but remember the one thing the world hates is a woman who minds her own business. They are telling awful things about me.

Martha Jane Cannary (1856 – 1903) (connue sous le nom de Calamity Jane) lettres à sa fille Jane 1895.

About Mother and Daughter II

What are these bodies doing? What figures are they creating? They are endlessly composing, decomposing, and recomposing the bond which unites them. A continual exploration of connections – this is perhaps how we could begin to describe the art of Diane Ducruet. In Mother and Daughter, she explores what connects and disconnects, what unites, and what divides. In the figures and forms that she (de)composes, she questions several enigmas: Family, origins, words, parts of the body, everything that devotes us to curiosity, exploration, representation, and the secrets of desire.

Endless metamorphoses

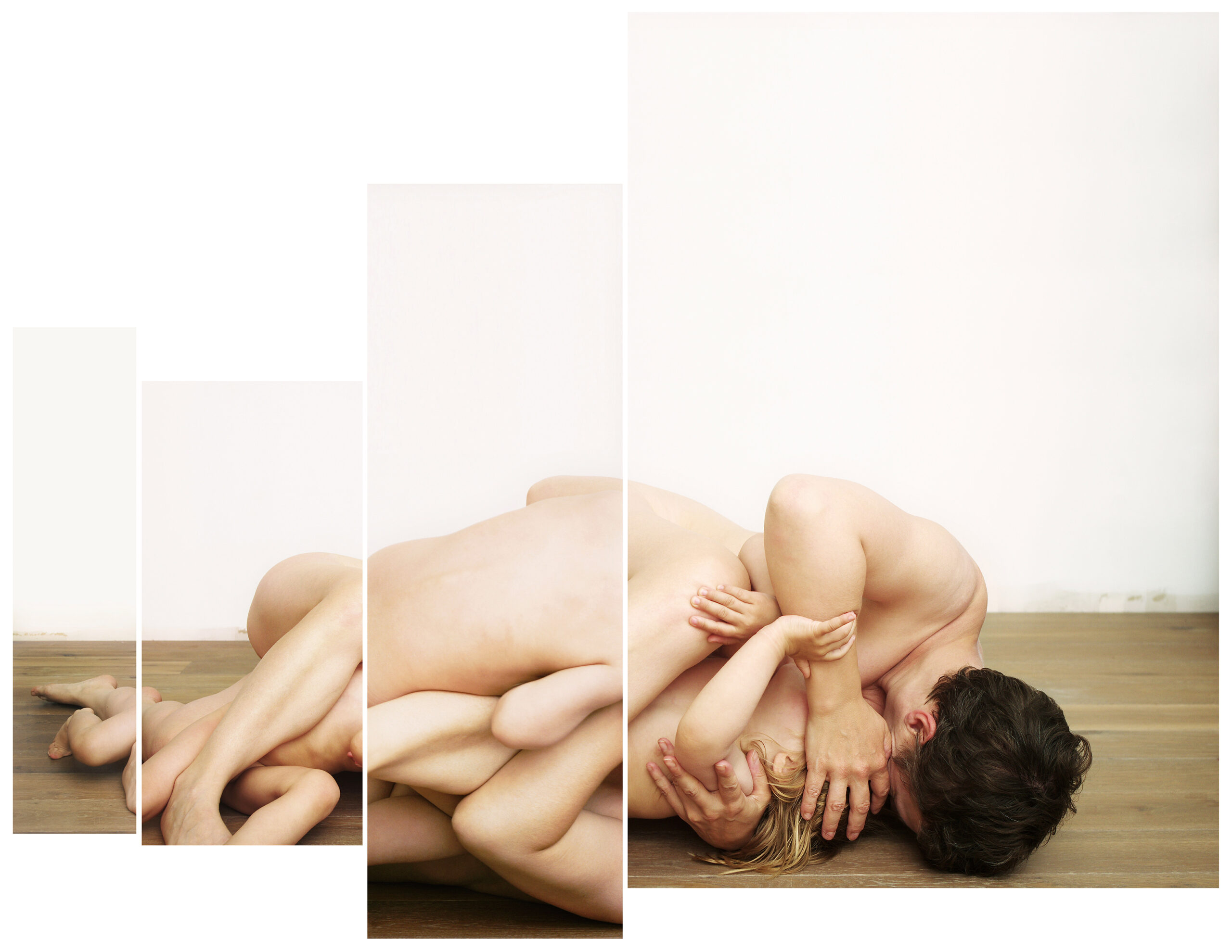

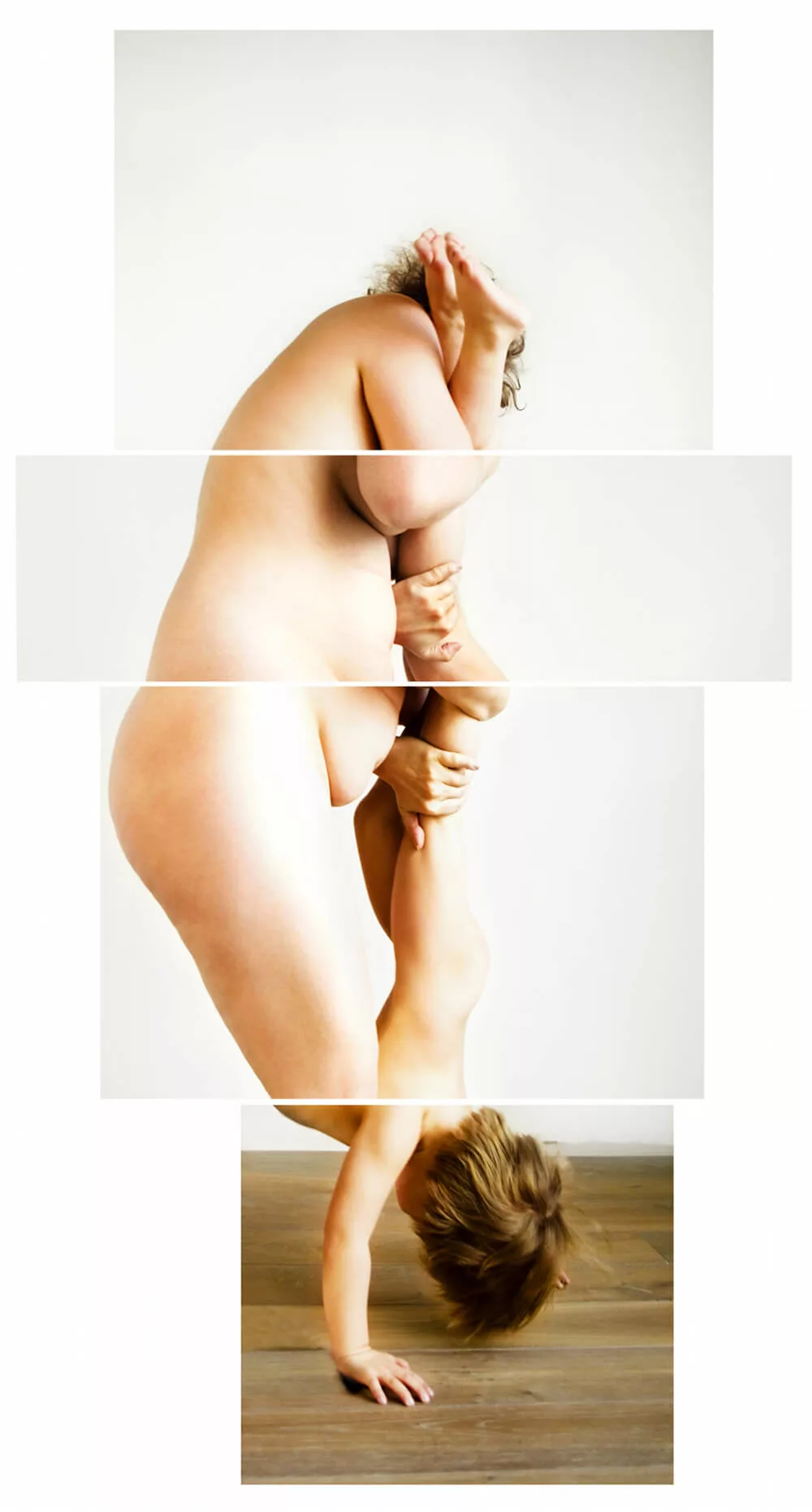

If, in her compositions, the body is the central theme – the body in its infinite possibilities, the body and its endless metamorphoses – it is to better redefine its center of gravity. It is to better distance ourselves from the weight of gravity and to propose a lighter alternative, a more playful one among the endless possibilities of connections and disconnections in a tender, teasing game of two. And so these two bodies, side by side, play at constructing and deconstructing, making a puzzle, twisting and turning, heads down, feet up.

They play on several dimensions and several levels. They bend, they interlock like acrobats, they walk a tightrope, they multiply before us, and then grow three heads. If the compositions of Diane Ducruet are in several parts, each element is alive. The bodies are not (re)composed randomly, even if the aesthetic surprises us. She makes a game of the montage, of the construction.

Ovid’s Metamorphoses

The question is one of displacement – strange bodies, loving, magnetic, a disturbed vision. It is through this experimentation that Diane Ducruet builds her images in the same way we dream. What we must retain above all is the temptation of the undecidable and the unpredictable. Man Ray said it in his famous anagram Image = magie (magic). And if magic is present here, it is because the artist/photographer succeeds in her double bet of making fun of gravity while reviving Ovid’s Metamorphoses.

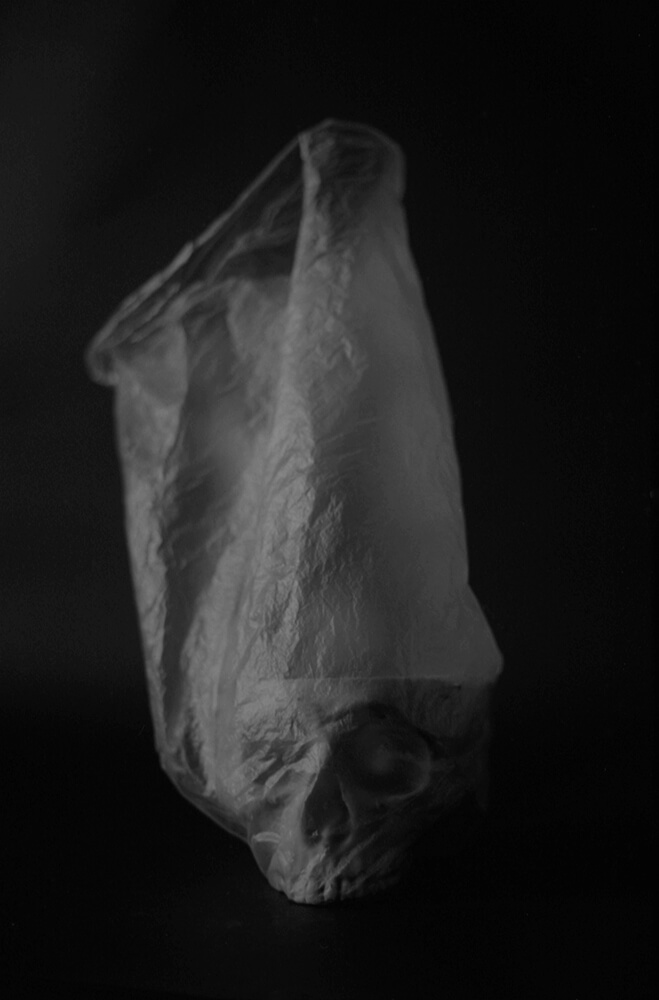

This is where we arrive at a different perception of time and space. Body parts melt away or disappear, squeeze, and deform. They are in constant permutations, the figures become confused as if subjected to the decomposition and recomposition of a surrealist dream. They almost create an enigmatic letter. A letter which is, like Pascal Quinard said, before all letters. It is the origin, the principal, the source, the matrix.

Puzzle

Is there a puzzle to be pieced together? Should we try to solve the rebus? How should it be read? The bodies are covered in enigmas and secrets, which the viewer tries to decode. As if behind them lay the secret of an anamorphosis or an anagram. Diane Ducruet consecrates her new work to the insecure articulation between incomparable, asymmetrical, and unopposable bodies. She replies in her own way to Aristotle’s essence of an enigma – trying to unite irreconcilable terms.

The images, as one might imagine, do not leave people indifferent. The fact that they depict two entwined bodies, albeit in a non-sexual encounter, does nothing to remove the fact that they bear the marks of taboo, of ambivalence. Because the union between these two bodies, a woman and a child, could be seen as incestuous, it has been read by some as strange, animalistic, and unjustifiable.

This opens the door to discourses of condemnation, censorship, and violence.

But what the censors want to censor is the representation of the sex drive of an intrusive phallic mother, surrounding, encircling, and devouring a little girl. A mother who is therefore not protective, but erotic, absorbing, sexual, and who would go as far as to want to return the fruit of her loin to her belly. But is that all there is here? Diane Ducruet’s photographs are certainly transgressive. This is why they are so powerful. This is how we can quantify their impact. She crosses a line. She goes beyond the question of good and bad. But the images are more than erotic provocation. They do much more than challenge the idea of incest. By challenging the oldest taboo, Diane Ducruet has created a highly poetic series. What they question is the unimaginable.

All pieces of the same whole

The nudity of the bodies is perhaps what has offended some spectators, but primarily, and by definition, she has returned the body to a state of primary innocence. Something which the censors appear to have forgotten. Human contact is reduced to its simplest expression in its simplest state. Love is expressed through cuddles and hugs – an attempt to create a unity that will never exist. Moreover, the distinction of the bodies is jumbled – yet the viewer is not completely in the dark – hand for a hand, head for a head, foot for a foot, the same skin tone. They are all pieces of the same whole. The depiction of the entangled bodies of this woman-child is assembled yet unassembled. They are a puzzle to be reassembled.

In today’s climate, it is daring to depict nudity.

In today’s climate, it is daring to depict nudity. Not genital, or sexual nudity, but the bond of incorruptible unity – the bond with infancy, with the family or femininity and their different aspects. Diane Ducruet’s work has nothing to do with breaking religious taboos, playing with sin or guilt, or depicting eroticized images.

It is about rediscovering an alliance that connects us all to infancy and the mother. Is it an embrace to reunite or clinging on so as not to lose?

We should perhaps add that childhood is an essential aspect of our dreams and of artists’ creativity. If the family is a vital part in the imagination of the photographer, it is just as important as a camera for the creative process. Whatever feeds the physical or family life is what also feeds the artistic, creative life. We don’t need Freud to tell us that there is a living, dreaming and perhaps suffering child in us all. Diane Ducruet has taken this formula word for word and poetically incorporated this into her photography. This is her art. She uncovers what we have camouflaged, and captures a myth, a legend. Her work opposes the harsh reality of separation, opens a door, and exposes what we don’t want to see. From a dizzying height, she captures a second in eternity.

Catalogue Rabenmütter Zwischen Kraft und Krise: Mütterbilder von 1900 bis heute, Exposition du 23.10.2015 – 21.2.2016 au LENTOS Kunstmuseum Linz – Autriche.

Eye for an eye

This is how Diane Ducruet invites us into the mouth of the lion. Literally. A powerful, terrifying image that makes the viewer shiver. The Lion – the lion who knows no fear, the lion of myth, the splendid elegant lion. And what of the child who puts her head into her mother’s mouth, what does she see? Is this not how the child might catch a glimpse of the bottom of her mother’s heart? She is taking a risk. And as Hélène Cixous would say, the risk is worth it. Diane Ducruet belongs to the family of artists who, to borrow Cixous’s phrase, create images that roar. Images that call for the liberation of all the prisoners of clichés. That is all of us. What better medium than photography? Eye for an eye, cliché for a cliché.

How can the viewer not take the bait?

I think of Diane Ducruet’s images when I read what Hans Bellmer wrote in L’ Anatomie de l’image.

‘The body is like a sentence which asks to be broken down and recomposed, through an endless series of anagrams, in order for its true contents to be discovered.’

Petite Anatomie de l’image, Hans Bellmer, Allia.

One must begin by playing the game rough and tumble to solve the riddle: My head is down in the morning, I have three heads at midday, and walk horizontally in the evening.

We look up, move our heads from left to right, and look in this muddle of bodies for what is played out and thwarted, said and unsaid.

a bow, a lion, a hydra, a centaur, a Cerberus, a cloud, or a column

We seek what makes it twist and turn and arch to become a bow, a lion, a hydra, a centaur, a Cerberus, a cloud, or a column. The figures, shining and airy, turn on themselves. Suspended. They become fantastical like meteors, upside down. Jubilantly they traverse the devenir and life itself. There is air. By animating these figures in space Diane Ducruet turns them into constellations. It is not only with the titles that Diane Ducruet leads us to this magical space of a poetic work.

A constellation

We could let ourselves believe that with these titles Diane Ducruet belongs to that poetic family of illusionists, those two have the gift of making stars appear and then vanish. The Bow (of Sagittarius), Leo, Lernaean Hydra, Centaur, Cerberus, (Hercules’s) Column, and (Magellen’s) Cloud are all constellations in the Milky Way. Milky way, maternal way, feminine voice. Each photo is a constellation, which has a link, directly or indirectly with the others. And so the cartography unfolds before our eyes. One becomes many – multiple combinations of bodies and meanings and forms. Diane Ducruet has reinvented the stars.

BOULARD Stéphanie (2015). Mother and Daughter II de Diane Ducruet. Ars Victoria Verlag, Siegen , 2015, 26–31. Traduction anglaise Matthew Douglas Kay.

Impression jet-d’encre sous diasec monté sur dibond aluminium différents formats, 2015.

« Super Mom oder kinderlos? Es scheint, als gäbe es kein selbstverständliches Muttersein mehr, nur Perfektion oder Verzicht. Doch die Mutterrolle hat viele Facetten: Freude, intensive Lebenserfahrung, Liebesbeziehung, Lernen, Übermut – aber auch Frust, Erwartungsdruck und Versagensangst. Im 19. Jahrhundert wurde Mutterschaft kaum in Frage gestellt,

auch wenn die Überhöhung des Mutterglücks im krassen Gegensatz zur Realität stand. Erst mit Karrieremöglichkeiten für Frauen entstanden Alternativen zur Mutterschaft als Ziel eines erfüllten Lebens. »

Introduction à l’exposition Rabenmütter Zwischen Kraft und Krise: Mütterbilder von 1900 bis heute, Exposition du 23.10.2015 – 21.2.2016 au LENTOS Kunstmuseum Linz – Autriche.